History of Community Health Centers

Community health centers have a rich history, particularly in Massachusetts where the first health center in the nation was launched in 1965. Following is a comprehensive account of community health centers up through the present.

In the Beginning: Launching a Movement

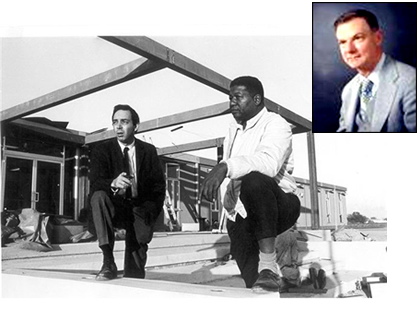

Physician-activists H. Jack Geiger and Count D. Gibson Jr. helped launch the American Community Health Center Movement 50 years ago with their founding of the first two community health centers in the nation: one in the Columbia Point section of Dorchester, and the other in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. Despite five decades of political, social and economic challenges, community health centers have remained committed to their mission of providing accessible, affordable and high-quality health care for all, growing from a two-site demonstration project to what is now the largest unified primary care network in the United States.

Pioneering Efforts: Improving Health Care for the Underserved

Before the community health center movement, accessible health services for low and moderate-income people were difficult to find. Where services did exist they were often characterized by long travel and waiting times, episodic and inefficient care and, in the worst instances, disrespect. Based on his observation that "the poor get sicker and the sick get poorer," Geiger, along with Gibson, helped to launch a revolution in health care delivery. Their belief -- that poverty-causing conditions must be addressed before the health of a community can be sustained -- formed the basis of the community health center model.

VIDEO: 'Out in the Rural | A Health Center in Mississippi' - Video courtesy of Delta Health Center, Mound Bayou, Mississippi; Tufts Medical School; H. Jack Geiger, MD

In the meantime, President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty, a broad-based social program to promote revitalization and economic development within urban and rural areas, was getting underway. The federal Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) -- charged with advancing Johnson's poverty initiative -- provided funding for the first two community Health Centers. The first opened at Dorchester's Columbia Point in December of 1965 and a second was established in Mound Bayou, Mississippi a year later.

In 1966, Senator Edward M. Kennedy visited Columbia Point and was so impressed with its community-based model of care that he urged the OEO to fund more centers across the country. Soon thereafter, health centers were funded in Denver, Chicago and New York City through a $38 million appropriations bill spearheaded by House Chair Adam Clayton Powell (D-New York) and Senator Kennedy. By 1971, there were 150 health centers throughout the country; 17 of those centers were located in Massachusetts.

Program Highlights: Surviving and Thriving through the Decades

Providing a forum and "branding" a movement

Six years after the founding of Columbia Point, health centers joined with public agencies and other

community-based health organizations in a conference held at Northeastern University to address the coordination

of public health planning for the city’s neighborhoods. As a major outcome, the Massachusetts League of

Community Health Centers (the League) was formed in 1972 to help define health centers as a network of

community-focused providers and to establish a forum for addressing their common needs and concerns. Subsequently,

the League and similar state associations helped found the National Association of Community Health Centers

(NACHC), established to provide technical assistance and advocacy for the centers at the national level.

Six years after the founding of Columbia Point, health centers joined with public agencies and other

community-based health organizations in a conference held at Northeastern University to address the coordination

of public health planning for the city’s neighborhoods. As a major outcome, the Massachusetts League of

Community Health Centers (the League) was formed in 1972 to help define health centers as a network of

community-focused providers and to establish a forum for addressing their common needs and concerns. Subsequently,

the League and similar state associations helped found the National Association of Community Health Centers

(NACHC), established to provide technical assistance and advocacy for the centers at the national level.

Threat of program elimination and later, block grants

However, support for the community health center movement was not always unanimous. As health centers across

the country became an increasingly cohesive national movement, they faced several challenges to their federally

funded grant program. In 1975 the League worked with Senator Kennedy and NACHC to beat back the first threat to

health center funding when President Gerald Ford's Administration proposed eliminating the program altogether.

In the end, the health centers not only had their funding restored -- they secured enough broad-based support to

obtain their first congressional authorization. Later in 1981 and again in 1995, Congress considered the block

granting of health center funding. In both cases, passage of grants failed as national grassroots efforts to

ensure that the health center program remained a direct federal-local partnership prevailed.

However, support for the community health center movement was not always unanimous. As health centers across

the country became an increasingly cohesive national movement, they faced several challenges to their federally

funded grant program. In 1975 the League worked with Senator Kennedy and NACHC to beat back the first threat to

health center funding when President Gerald Ford's Administration proposed eliminating the program altogether.

In the end, the health centers not only had their funding restored -- they secured enough broad-based support to

obtain their first congressional authorization. Later in 1981 and again in 1995, Congress considered the block

granting of health center funding. In both cases, passage of grants failed as national grassroots efforts to

ensure that the health center program remained a direct federal-local partnership prevailed.

1980s bring managed care, a new health plan and recognition of the plight of the uninsured

It was in the early 1980s that

managed care began to take hold in Massachusetts. In an effort to remain competitive and to ensure health access for the most

vulnerable, the League joined with Boston business leaders in 1986 to help found the community health center-based HMO,

Neighborhood Health Plan. Around the same time, health centers were treating an increasing number of uninsured patients, then

Governor Michael Dukakis was running for President and the state legislature was crafting a universal health care plan for

Massachusetts. Making the case that health centers could expand care to the growing uninsured and steer people away from costly

hospital emergency rooms, health centers gained the support of business leaders and policymakers. As a major result, by 1991

health centers became eligible providers of care through a new state uncompensated care pool designed to pay for the medical

costs of uninsured Massachusetts.

It was in the early 1980s that

managed care began to take hold in Massachusetts. In an effort to remain competitive and to ensure health access for the most

vulnerable, the League joined with Boston business leaders in 1986 to help found the community health center-based HMO,

Neighborhood Health Plan. Around the same time, health centers were treating an increasing number of uninsured patients, then

Governor Michael Dukakis was running for President and the state legislature was crafting a universal health care plan for

Massachusetts. Making the case that health centers could expand care to the growing uninsured and steer people away from costly

hospital emergency rooms, health centers gained the support of business leaders and policymakers. As a major result, by 1991

health centers became eligible providers of care through a new state uncompensated care pool designed to pay for the medical

costs of uninsured Massachusetts.

Health centers come full circle as they emerge once again as a solution for expanding health access

In the early 1990s, there was considerable consensus among public health advocates to promote the idea that a tax on cigarettes was a necessary and just approach to funding public health programs. In 1992, Massachusetts' voters overwhelming approved a ballot initiative to place a 25-cent per pack tax on cigarettes programs focusing on smoking prevention and cessation.

In 1996, another 25-cent per pack increase was supported by a broad-based coalition, including the League. The intent was to use cigarette tax revenues to expand eligibility for the state's Medicaid program, and for creation of a second plan to cover children whose families' incomes were too high to qualify for Medicaid. The culmination of these efforts resulted in passage of M.G.L. Chapter 203, the 1996 landmark legislation that extended Medicaid coverage to more low-income Massachusetts residents. In order to find and enroll the newly eligible residents, state officials turned to community health centers. By 2002, health centers had helped to enroll 300,000 new people into the Massachusetts' Medicaid program and had gained recognition as a solution for expanding care to low-income patients as a result of their accessible, quality and cost-effective care.

CHCs Today: Adapting to Change, Sustained by Mission

Today, the state's 50 community health center organizations provide care to one out of every seven people (951,000 state

residents) through more than 285 total access sites across the state. These sites offer primary, preventive and dental care, as

well as mental health, substance abuse and other community-based services to anyone in need regardless of insurance status or

ability to pay. Nationally, health centers total more than 1,3100 and serve more than 25 million people.

Today, the state's 50 community health center organizations provide care to one out of every seven people (951,000 state

residents) through more than 285 total access sites across the state. These sites offer primary, preventive and dental care, as

well as mental health, substance abuse and other community-based services to anyone in need regardless of insurance status or

ability to pay. Nationally, health centers total more than 1,3100 and serve more than 25 million people.

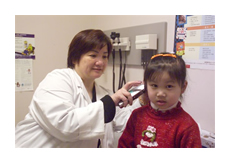

Massachusetts community health centers care for patients of all ages and racial and ethnic backgrounds, and represent a major source of care for medically underserved women and children. Health center patients are disproportionately low-income, publicly insured or uninsured, and are at higher risk for contracting chronic and complex diseases. Ninety percent of health center patients have incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level or $47,100 in annual income for a family of four. Sixty-three percent of Massachusetts health center patients belong to an ethnic or racial minority group.

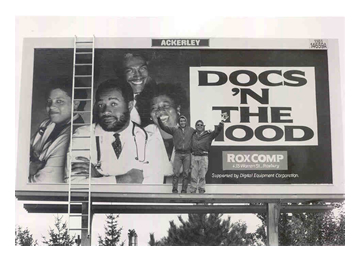

Consumer Based Governance

While many health care organizations talk about being consumer or patient focused, few have institutionalized that commitment to the same degree as community health centers. The belief that community members can play a direct role in improving their life circumstances, including health status, was the driving force behind the health center model. Health center boards of directors continue to be driven by community members who receive care through their local health center.

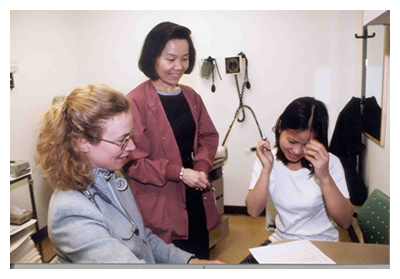

Linguistic and Cultural Competency

As the racial and ethnic diversity of Massachusetts' communities has increased over the past several decades, community health centers have evolved to meet the needs of changing patient populations. More than 39 languages are spoken by health center staff or available through interpreters. The success of community health centers in reducing racial and ethnic disparities has been documented in dozens of national studies.

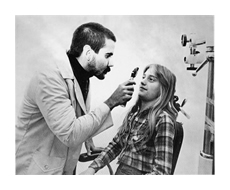

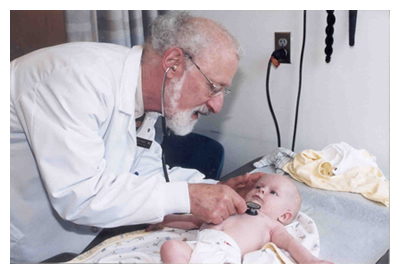

Accessible, Quality Care

Community health centers are receiving increasing attention as a solution for reducing health costs and ensuring health quality in Massachusetts and across the nation. There are dozens of national studies on the cost-effectiveness and quality of care provided by community health centers and their demonstrated and historic savings to state Medicaid programs and other insurers.

Patients served by community health centers have complex medical and social needs that can make adherence to prevention and medical treatment plans more difficult. Innovative health center programs in prenatal care, cancer prevention, pharmacy management, snd chronic disease management improve the health of patients and can reduce reliance on higher cost emergency department and hospital care. Health centers also provide extensive outreach and enrollment assistance services to ensure that patients can access the public and private health insurance programs for which they are eligible.

Economic Engines

In addition to their health and social service roles, health centers are stable community assets that operate as economic development engines within low-income communities by producing goods and services; offering critical entry-level jobs, training, and career building opportunities that are community-based; and serving as anchors for attracting new businesses and investments into the community. In 2013, Massachusetts health centers generated 12,000 full-time jobs, $1.86 billion in expenditures and $1.1 billion in annual savings for the Commonwealth.

Looking to the Future: Meeting New Challenges and Opportunities

Working on the frontlines of state efforts to implement near-universal health coverage, community health centers are ensuring access for Massachusetts’ residents to timely, ongoing primary and preventive care. Focused on health promotion and disease prevention, community health centers continue to tackle some of the most complex public health issues of our time. Serving communities that are disproportionately affected by the challenges of poverty, chronic diseases like diabetes and asthma, and a longstanding lack of access to health services, community health centers are making an impact in three important ways:

- Offering Critical Health Access: Improving the health of medically underserved communities.

- Providing High Quality, Cost-Effective Care: Producing savings for taxpayers and insurers through the provision of timely, high quality primary and preventive care.

- Serving as Economic Engines: Stimulating economic output in low-income communities hit hard by the economic downturn.

Health care reform efforts can build on the success of the health center movement over the past forty years and ensure that our most vulnerable residents will have access to high quality, comprehensive health care in their own communities. With sufficient reimbursement and investments in infrastructure, Massachusetts health centers could expand capacity, relieve many of the burdens on our over-stressed health system and help make affordable, accessible health care a reality for all of Massachusetts' residents.